“You can’t go back home to your family, back home to your childhood … back home to a young man’s dreams of glory and of fame … back home to places in the country, back home to the old forms and systems of things which once seemed everlasting but which are changing all the time – back home to the escapes of Time and Memory.”

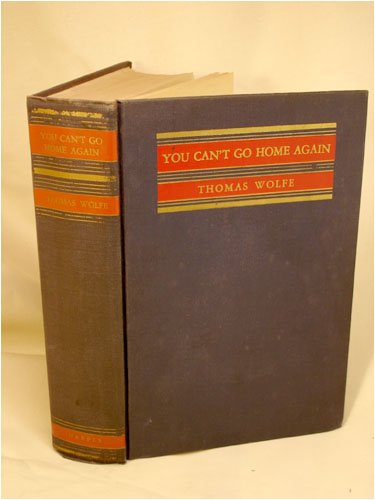

Published in 1940, two years after the loquacious author Thomas Wolfe unexpectedly died, You Can’t Go Home Again belongs to a select group of novels whose title has entered American speech as a catch phrase. Catch-22 also enjoys this status of being a book few have read but we all seem to use the phrase in daily life with a winking acknowledgment.

We all know what “you can’t go home again” means, but a deeper understanding of the sentiment behind the phrase yields a bountiful crop of compassionate undergrowth.

To begin with the obvious, anyone returning to their hometown following a period away notices the changes. Gone is the local drug store, replaced by a pharmacy chain. Gone is the chain toy store you once protested against when it bought out the local toy store. Gone is the barber shop at which you used to get your hair cut, where they had to use the booster seat to allow you to sit high enough for the barber, who doubled as your neighbor. Mom and Pop stores are eaten by chains, which are, in turn, swallowed by larger chains; themselves prey to the threat from the internet and online shopping. Sure, the ice cream parlor still remains, but the menu has changed, the furnishings updated, the uniforms different and the charm captured by childhood gone. Restaurants change name, fields become strip malls and the potato farm beyond the outfield has grown into a neighborhood.

Still, the phrase refers to to time not distance or travel. How often is the frustration of the dieter who weighs themselves daily validated by the comments of those who do not see the individual on a daily basis? How many times do we catch our reflection in the morning mirror wondering who that old person is staring back? So too, is the change of “home” incremental yet perpetual. Daily life contains checklists, both mental and written, which drive our actions.

- Get up at 6:00, eat breakfast, shower, shave, dress

- Run to the supermarket (we need bananas and bread (critical))

- Must stop at the Post Office to drop off the package to ensure it arrives at Aunt Clara’s before her birthday on Tuesday

- I’d like to get to Barnes & Noble to pick up that new book Charlie was raving about

- Dinner with the group tonight (whose house is it at?)

- Get to bed at a “decent” time tonight. That twitch in my lower eye lid is driving me crazy.

Seldom do we slow down enough to see how much has changed. Perhaps this is done on purpose. Each of us carries a mental picture of everyone else in their mind. Ask yourself, “When was this “picture” snapped?” My image of my grandfather (my father’s father) was snapped in his basement, hovering over his workbench. When was that? 1970-something? My image of my grandmother (my father’s mother) is of her sitting at her kitchen table scratching at the incessant itching in her hands, offering me one snack after another. When was that? My image of my other grandmother (my mother’s mother) resides in actual snapshots; photographs I’ve seen which merge with stories I’ve heard from those older than me, and thus capable of holding a memory. And so it is with everyone I’ve ever met. Name someone and I will unconsciously recall a moment in time and an age of that person at which they are forever frozen. This is one of the conundrums I have with the concept of heaven. Should I die and be admitted to the ultimate club and see my paternal great-grandmother (who, in my youth seemed to be Methuselah’s age when she died), how old would she seem to me? And at what age would she appear to her great-grandmother who died when my great-grandmother was in cloth diapers in Italy?

Memories rush up to meet us without recall demands made; the mystique of “family” softened by the endless waves of time. There is a promontory rock in my hometown against which an endless line of waves crash. This rock has endured wave upon wave since before my birth and will endure them for countless millennia after I die, with little change to the rock. Ovid said, ““Dripping water hollows out stone, not through force but through persistence.” Persistence measured in thousands of years eludes my capacity of comprehension.

And while Main Street changes over time, we cannot forget that it is a two-way street. Those exposed to the daily changes accept them as the new “normal.” Times change and we have to keep up! The reinsertion of the returning local into this new equation causes an unintentional sheering of expectations from memory. The resident expects the returning friend/relative to merge with the existing daily life to which they have become accustomed through the gradual hollowing out of the stone of the local landscape. The collision of the returning individual’s memory with the resident’s daily reality, coupled with the mental image we carry of the individual, can yield conflict and confusion. Family mystique is usually best carried by those who have physically had to relocate. A myth develops over time of something the individual perceives as having been taken from them, whereas the reality is simply human beings in one small community clashing and embracing, subject to the baggage we all carry. Grudges are held, “hatred” festers, blame is assigned and emotional distance creates a gulf where no physical distance exists. To the physically removed family member, these animosities seem petty and counterproductive. Consider the view of the astronaut aboard the International Space Station looking through the port hole at the earth as it passes constantly from daylight into night and back again. How meaningless do our conflicts seem from afar? How insignificant do national borders seem, religious differences resulting in warfare, the skin color or sex of one ant from another? Unfortunately, few of us have the ability to step back and observe from such a height, even figuratively. Wolfe expands upon his catch phrase below:

Some things will never change. Some things will always be the same. Lean down your ear upon the earth and listen.

The voice of forest water in the night, a woman’s laughter in the dark, the clean, hard rattle of raked gravel, the cricketing stitch of midday in hot meadows, the delicate web of children’s voices in bright air–these things will never change.

The glitter of sunlight on roughened water, the glory of the stars, the innocence of morning, the smell of the sea in harbors, the feathery blur and smoky buddings of young boughs, and something there that comes and goes and never can be captured, the thorn of spring, the sharp and tongueless cry–these things will always be the same.

All things belonging to the earth will never change–the leaf, the blade, the flower, the wind that cries and sleeps and wakes again, the trees whose stiff arms clash and tremble in the dark, and the dust of lovers long since buried in the earth–all things proceeding from the earth to seasons, all things that lapse and change and come again upon the earth–these things will always be the same, for they come up from the earth that never changes, they go back into the earth that lasts forever. Only the earth endures, but it endures forever.

The tarantula, the adder, and the asp will also never change. Pain and death will always be the same. But under the pavements trembling like a pulse, under the buildings trembling like a cry, under the waste of time, under the hoof of the beast above the broken bones of cities, there will be something growing like a flower, something bursting from the earth again, forever deathless, faithful, coming into life again like April.”

Can all of this be summarized as “stop to smell the roses?” Maybe, but we never seem to take the time to add it to our list of things to do.

We can go home again, if only in our memories, and there, we have never left.